by Will Beaman

W.E.B. Du Bois’s “psychological wage” has long been treated as a metaphor. In Black Reconstruction, he describes how white workers, denied meaningful economic uplift, found compensation in racial status. Many have read this as a bribe, or as a symbolic reward for class betrayal—something less real than money, but no less effective in dividing the working class.

That reading rests on a familiar split between the psychological and the material. Racial esteem appears as an illusion, set against the tangible structures of wages, land, and capital. Even more sympathetic interpretations tend to preserve that hierarchy: psychology may be powerful, but money is what counts.

But Du Bois’s phrase does not merely point to a parallel between money and status. It stages something more robust and flexible than a metaphor: an analogy. Not a substitution of likeness, but a choreography between forms. The psychological is not “just as real” as the material. It is staged as material across institutions.

This is not quite Du Bois’s own argument. He did not frame whiteness as a currency, nor was he writing from a theory of endogenous credit—that is, a view of money as something issued, distributed, and coordinated from within social and institutional life. But his formulation invites such a reading for those who are looking for it. This is a reparative approach: not an attempt to retrofit Du Bois into a monetary theory he did not share, but to extend the intuitions that his concept makes available to us, and to trace how they resonate within a broader politics of credit and recognition.

The psychological wage, on this reading, is not a stand-in for economic life. It is one of its currencies: a system for distributing value, legitimacy, and access. It operates within, against, and alongside the dollar—sometimes underwriting its effects, sometimes shaping them in more violent or distorted directions. Whiteness, in this frame, functions as a rogue issuance structure: a mode of provisioning that overlaps with official systems, but is never fully secured by them.

To trace this choreography is not to reduce value to a single structure or contradiction. It is to notice how value is staged and restaged across domains—how public life is assembled through overlapping genres of credit and belonging. Whiteness is one of those genres, and its wage is not a metaphor. It is a script, a system, and a currency. And it is improvised, rehearsed, and enforced in unequal measure.

Rogue Issuance and the Choreography of Credit

If the psychological wage is a currency, it is one that does not circulate on its own. Like the dollar, it must be issued, accepted, and reissued. Its legitimacy is never self-evident. It relies on rituals—public scripts that coordinate belief, recognition, and value across domains. What Du Bois observed was not just a compensatory self-image, but a system of provisioning: a choreography of credit that names, elevates, and withholds.

This is the sense in which whiteness acts as a rogue issuance structure. It confers permissions—who is employable, electable, presumed competent or harmless—and it denies them. It rehearses who can be trusted with leadership, housing, and grace. Its credit regime is rarely codified, but it is widely rehearsed and reinforced through credentials, reputations, and soft evaluations. It sanctions not only behavior but being, reinforcing a sense of deservedness through moral idioms like work ethic, family values, and lawfulness. Whiteness, as a set of public rituals, permits the dollar in some contexts, supplants it in others, and blocks it elsewhere.

To name whiteness as a currency is not to ennoble it, or to deny the fragility and violence of the value it provisions. The forms of receivability it sustains—access to housing, credibility, or bodily safety—are pathologically unstable, rooted in exclusion, resentment, and myths of deservedness rather than in durable public life. This instability is not a flaw but a feature of its affective infrastructure. As Du Bois recognized, it binds social life by staging threat and reward along racial lines. But whiteness does not merely console the dispossessed. It conditions value itself—including among the wealthy, who are often provisioned not with security but with paranoia, grievance, and moral license. Its currency scripts legitimacy through volatility and rehearsed threat, across contexts differently staged as privilege or precarity.

None of this occurs outside the terrain of the dollar, as this suggests. But the dollar itself is not a coherent entity. It is already a choreography: a composite of coins, notes, deposits, reserves, and credit instruments—issued across the balance sheets of banks, treasuries, courts, and municipal governments, each with their own histories, idioms, and institutional rhythms. It has never been a single thing.

Its seeming continuity is an effect of coordination—an aesthetic and procedural labor that must be sustained. Whiteness and the dollar, then, are not the same. But they are not separable. They pass through one another. From the redlining of neighborhoods to the algorithmic scoring of creditworthiness, monetary systems have always embedded racial logics of credibility and threat. The infrastructure of whiteness has helped determine which expenditures are seen as investment and which as waste, which lives are worthy of public guarantees and which are overdrawn by default.

To understand this convergence requires attending not just to violence and exclusion, but to narrative and form. Whiteness functions not as an illusion or conspiracy, but as a genre of continuity. It makes disjointed provisions feel seamless. It codes asymmetric inclusion as natural legitimacy. It smooths over the cracks between property, personhood, and security. In this way, it choreographs the alignment of public life with itself—not through mastery, but through the repetition of a script that demands constant performance.

And because that performance disavows and conceals itself, whiteness as a currency is always under stress. What whiteness stages as self-evident has to be vigilantly enforced, patrolled, and defended. It improvises stability by invoking threats and scapegoats. It requires moral panics and narrative resets to cover over its breakdowns. Its continuity is not a given, but a fragile project. And when its claim to stable continuity falters, its most invested participants improvise new affective infrastructures to make the pain go away. That is Trumpism. But before Trump, this logic of continuity has been traceable across diverse aesthetic forms: homeownership, suburban coherence, and the smoothing operations of narrative itself.

Staging Continuity

Whiteness does not operate only through force—it relies on form. Across the 20th century, institutions stylized continuity: mortgages, suburban zoning, credit markets, and municipal budgets did not just allocate resources. They offered genres of legitimacy. Financial scripts taught people how to live, while aesthetic scripts trained them to see value, coherence, and threat.

Homeownership was central to this process. As historian David M. P. Freund shows in Colored Property, federal housing policy did not simply grant white families access to homes. It constructed a credit-based infrastructure that linked whiteness to financial credibility. Banks, zoning boards, and insurance tables embedded racial exclusion into public finance. What appeared as market rationality was a selective choreography of trust—coded as neutrality, rehearsed as meritocracy.

Creditworthiness, in this landscape, became a moral genre. Beyond shelter, homeownership staged stability, future orientation, and civic belonging. It made whiteness appear prudent, deserving, and low-risk. Public life was organized around this appearance. And to sustain it, credit systems needed ways of managing discontinuity: foreclosure, disinvestment, labor displacement, racial integration. These ruptures had to be smoothed over or re-narrated.

That smoothing work did not begin with housing policy. Earlier techniques for managing discontinuity appeared onscreen, where the visual grammar of cinema trained audiences to perceive order in the midst of fracture.

The institutions of housing and credit were accompanied—and often conditioned—by visual forms that taught people how to recognize coherence where there was asymmetry. Chief among these was cinema. As the dominant narrative medium of the 20th century, film did not just depict public life—it organized its legibility. Its techniques of continuity editing taught viewers how to register coherence, resolve conflict, and align emotionally with dominant scripts of legitimacy.

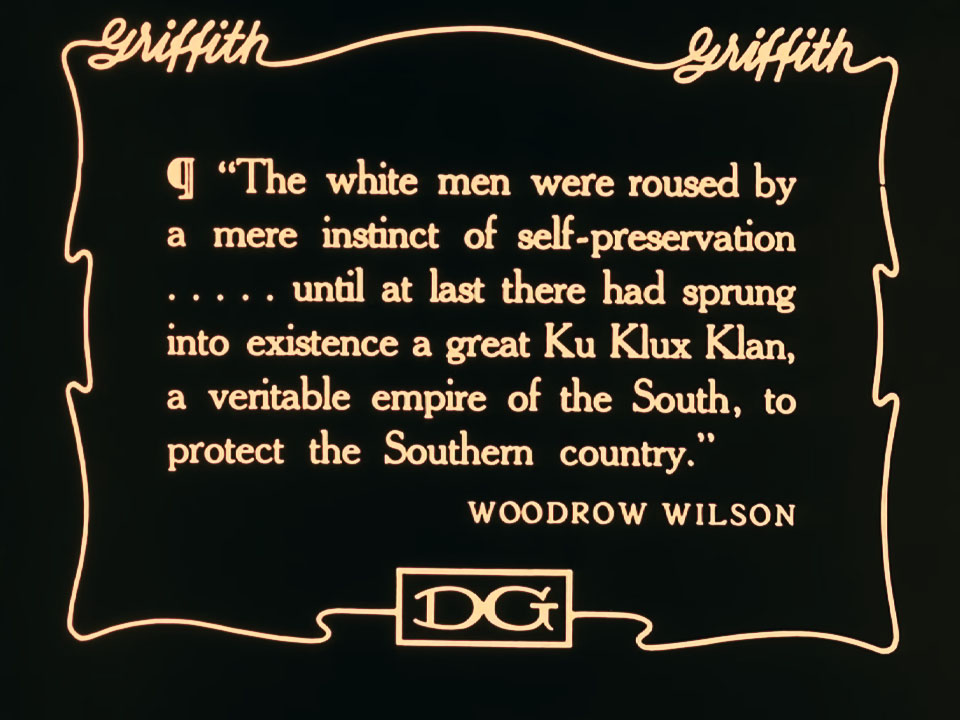

These techniques were crystallizing across early cinema, but The Birth of a Nation (1915) gave them their most influential and violent expression. The film did more than mythologize the Ku Klux Klan as redeemers of white civilization—it showcased an emerging grammar of cinematic continuity. Techniques meant to weave spatial and temporal continuity like match-on-action cuts, establishing shots, and crosscutting were becoming common across the industry, but here they were marshaled to render racial violence as narrative resolution. Early narrative films often staged trials, domestic order, and mob justice, turning moral panic into moral clarity through continuity techniques that led viewers through an unambiguous and seemingly undoctored social world.

The grammar of cinematic continuity was not incidental. It mirrored and anticipated the grammar of white fiscal governance. Where mortgage finance aligned whiteness with financial coherence, cinema rendered racial violence as narrative closure. Together, these infrastructures naturalized the distribution of value and threat. They made racial credit logics feel intuitive: who deserves a home, who appears as a threat, who merits rescue or redemption.

Like all systems of credit, narrative continuity requires labor. It must be sustained, defended, and updated. When dominant scripts break down—through economic crisis, political rupture, or affective dissonance—new infrastructures rush in to compensate. Trumpism was one such improvisation: a recalibration of whiteness’s issuance crisis.

Trumpism and the Collapse of White Credit

By the time Donald Trump descended his golden escalator in 2015, the infrastructure of white credit had begun to buckle. The housing collapse of 2008 had already exposed the racial asymmetries baked into homeownership and finance. Many white homeowners experienced foreclosure for the first time—an experience long familiar to Black communities. And yet the fallout was not interpreted as a failure of whiteness’s credit regime, but as its betrayal. What followed was not a reckoning with that regime’s selective provisioning, but a furious attempt to reclaim its authority.

Trumpism emerged as a performance of that reclamation. Its aesthetic was not continuity, but improvisation. It did not restore faith in institutions, but acted out their collapse. Its power came not from restoring legitimacy, but from redistributing permission: who could speak, who could offend, who could disobey. This was a shift in genre. If whiteness had long functioned as a currency of propriety, responsibility, and quiet entitlement, Trumpism offered its rogue variant—a high-yield bond issued in the voice of grievance and spectacle.

Trump did not invent this genre. He inherited it from decades of white reaction and expanded it into a total aesthetic. His rallies resembled wrestling matches more than speeches. His governance was theatrical and erratic. His authority came not from coherence but from affective asymmetry—punishment without principle, entitlement without responsibility. He flipped the script of white creditworthiness. No longer the silent majority, his base became the loud minority: proud to offend, eager to humiliate, impatient with anything that delayed gratification.

Trumpism did not restore the psychological wage. It performed its inflation. What once operated through subtle cues and institutional choreography now erupted into spectacle. This was not a revival of confidence in whiteness-as-credit—it was its liquidation.

Yet Trumpism also revealed what whiteness had always required: staging, repetition, narrative, and rehearsal. Even its most chaotic expressions still followed a script about grievance, betrayal, redemption, and retribution. And like all currencies, it demanded belief. The improvisation only worked because it felt authorized. It gave its audience not new power, but the feeling of having never lost it.

What came into view in this moment was not the end of white issuance, but its reformatting. Trumpism did not undo the dollar. It did not replace the mortgage or the budget or the suburban imaginary. It added to them a new affective overlay—a vigilante infrastructure of vibes and vengeance, broadcasting its legitimacy through volume and pain.

The Tea Party movement began reissuing the psychological wage in a new fiscal and affective register. In the wake of the 2008 housing crash, white grievance congealed not around foreclosure itself, but around the fantasy that “undeserving others” had disrupted the moral logic of debt and reward. The Obama administration’s efforts to manage the crisis—via stimulus, bailouts, or mortgage relief—were reframed as theft from the “real” public: a racialized middle class whose creditworthiness had long been naturalized. Birtherism, with Trump as its most theatrical spokesman, extended this suspicion from the mortgage to the presidency. It questioned not only Obama’s origins, but the very legibility of Black legitimacy within white fiscal order. This was not yet Trumpism, but its grammar was already there: suspicion, spectacle, entitlement, and the demand to be visibly re-centered.

Trump did not introduce spectacle into whiteness; he made visible what had long been disavowed. Earlier forms invited white audiences to consume racial violence as spectacle in order to condemn it—reveling in fantasies of threat and punishment while insisting on their own moral distance. Trumpism recasts that enjoyment as its own justification.

That shift—from disavowed enjoyment to open indulgence—is not a departure from whiteness’s affective infrastructure but a symptom of its breakdown. Trumpism draws on fantasies long rehearsed in unconscious form, but restages them compulsively, as volatility, grievance, and spectacle become the means by which whiteness shores up credibility to itself and others.

But the improvisation did not come out of nowhere—and it did not arrive fully formed. It built on existing scripts of entitlement and threat, pushing them past narrative restraint into open-ended spectacle. What had once been managed through veiled cues and institutional choreography now roared through crisis aesthetics. The story no longer resolved; it repeated, frayed, and spiraled.

Trumpism and the Performance of Collapse

Trumpism did not restore the psychological wage. It performed its “inflation”—or at least, what felt like one. The term is often used to suggest that too much credit has flooded the system and eroded its value. But that is not how credit works. Value does not dilute from over-issuance alone; it breaks down when the systems that provision and coordinate meaning begin to fail. What we call inflation is often just that: a crisis in infrastructure, not in quantity.

Trump’s spectacle emerged in precisely this context. The longstanding infrastructures that sustained whiteness—housing, employment, national myth—had begun to collapse under their own contradictions. Epstein’s exposure did not just implicate Trump personally. It broke the script. It made visible the gap between permission and legitimacy, between continuity and the structures that had always provisioned it. Trump’s response was not to restore order, but to stage its unraveling as catharsis.

This was not a revival of confidence in whiteness-as-credit. It was a performance of collapse: flags, chants, humiliation rituals, and gaudy excess. The affective architecture of whiteness, long managed through understated cues and institutional discretion, now roared through spectacle. Not because whiteness had been devalued by overuse, but because its continuity could no longer be convincingly choreographed.

Like housing and like cinema, Trumpism attempted to stage coherence out of fragments. But where Hollywood once smoothed those fragments into a narrative of order, Trump leaned into the jaggedness. Scandal did not replace plot; it rose to the fore. Early narrative films indulged spectacle, exploitation, and scandal, but housed them within melodramatic storylines that gave audiences a way to feel unimplicated in those indulgences. Trumpism abandoned that narrative containment. The story no longer resolved; it repeated, frayed, and spiraled.

If the psychological wage was always currency, Trumpism was its dramatic foreclosure notice. Not a new issuance, but a desperate demand for back pay. The spectacle was not redemptive. It was an attempt to feel like something still backed that credit, even if all that remained was grievance and noise.

That script cannot remain the same. The infrastructure that once choreographed legitimacy through restraint and propriety now improvises through excess, repetition, and pain. Trumpism did not sever the provisioning of whiteness—it restructured it around performance, resentment, and spectacle. The credits are still being issued. The roles are still being cast.

Rogue Affect and the Aesthetics of Issuance

The fantasies of rogue issuance that simmered beneath mid-century white prosperity—always latent in the figure of the self-made man, the bootstrapped homesteader, the frontier entrepreneur—took on new affective labor during the neoliberal era, sustaining belief in whiteness-as-credit even as public imaginaries narrowed. After the 2008 collapse, these imaginaries found new institutional form in the rise of seemingly extra-institutional cryptocurrencies, which promised not only freedom from government but a sovereign infrastructure of value. These systems echoed white credit logics: exclusionary, performative, obsessed with authenticity and deservingness. Their fascist alignments sharpened over time, culminating in open grifts like Trump Coins—herrenvolk fantasy made liquid, a brazenly scammy frontier issuance of whiteness that made the scamminess the whole point.

The rise of crypto markets trading on “vibes” marks not the liberation of affect from institutions, but their rearticulation in unaccountable form. What looks like freedom from governance is really a displacement of it—reducing infrastructure to spectacle, and public trust to speculative mood. Affect has always helped coordinate credit, legitimacy, and trust—but within the racialized order of whiteness, it has been repeatedly disavowed: dismissed as mere sentiment when it surfaced outside sanctioned scripts, cast as volatility, mood, or threat. Crypto runs with that disavowal, converting scenes of trust and belonging into extractable fluctuations in sentiment.

Even on the left, affect is often prized for its escape from institutions—its ambiguity, unruliness, or refusal of legibility. But to treat affect as excess is to surrender its infrastructural power. What appears radical in its unruliness may unwittingly echo the right’s romance of unaccountability. Both suppress the need for accounting. Both rehearse an aesthetic of issuance that disavows responsibility. Crypto does not reject institutions; it reifies their coordinated exclusions as market outcomes, staging freedom as deregulated feeling and coherence as vibes.

The Next Script

The psychological wage was never a fixed promise or a permanent station. It was a fragile choreography—improvised, enforced, and rehearsed through everyday scenes of trust, threat, and belonging. Its power came not from what it was, but from how reliably it passed for something natural.

That reliability is faltering. Trumpism did not invent the breakdown; it emerged from it. As the institutions that once sustained white continuity began to unravel—housing, policing, media, civic order—so too did the ability to naturalize those provisions. What remains is not the absence of a script, but a scramble for new ones. A scramble to renew the feeling that one still belongs to something self-evident.

This collapse clarifies not only how whiteness operates, but what the concept of a wage might help us see. Du Bois named a structure of compensation and enforcement that was never merely symbolic, and never purely economic. He gave us a figure—a felt, distributed wage—that can be reread today as a clue to how value, legitimacy, and belonging are provisioned through institutional life. This essay has followed that clue, not to recover his meaning, but to build on its resonances: to reimagine the psychological wage not as a metaphor, but as a currency in its own right.

There is no undoing that history. But there is a responsibility that comes with knowing it. If whiteness has operated as a rogue monetary infrastructure, then refusing it means more than critique. It means building differently. It means designing public life with an eye toward recognition that does not demand erasure, toward coordination that does not require scapegoats, and toward accountability that is scripted through shared participation, with room for revision, complexity, and care.

Published by