by Will Beaman

A common refrain keeps surfacing among prominent journalists- and commentators-in-digital-exile on BlueSky. Commenting on the emergence of yet another shadowy centrist think tank, New York Times columnist Jamelle Bouie observes: “Trump’s numbers are tanking and there is a palpable desire in the electorate for a real alternative and yet the only money in democratic politics is for doing Starmerism.” Tim Carvell, a writer for Last Week Tonight with John Oliver, notes: “a legacy publication or a deep-pocketed investor could hire an astonishing array of talent right now and make the best newspaper in America overnight.” Ben Collins of The Onion puts it bluntly: “If you’re rich and not a coward, this is what you’d refer to as a ‘market opportunity’… to be a pop of color in a sea of beige will be easier than ever. People will flock to it. You gotta be a little brave, though.”

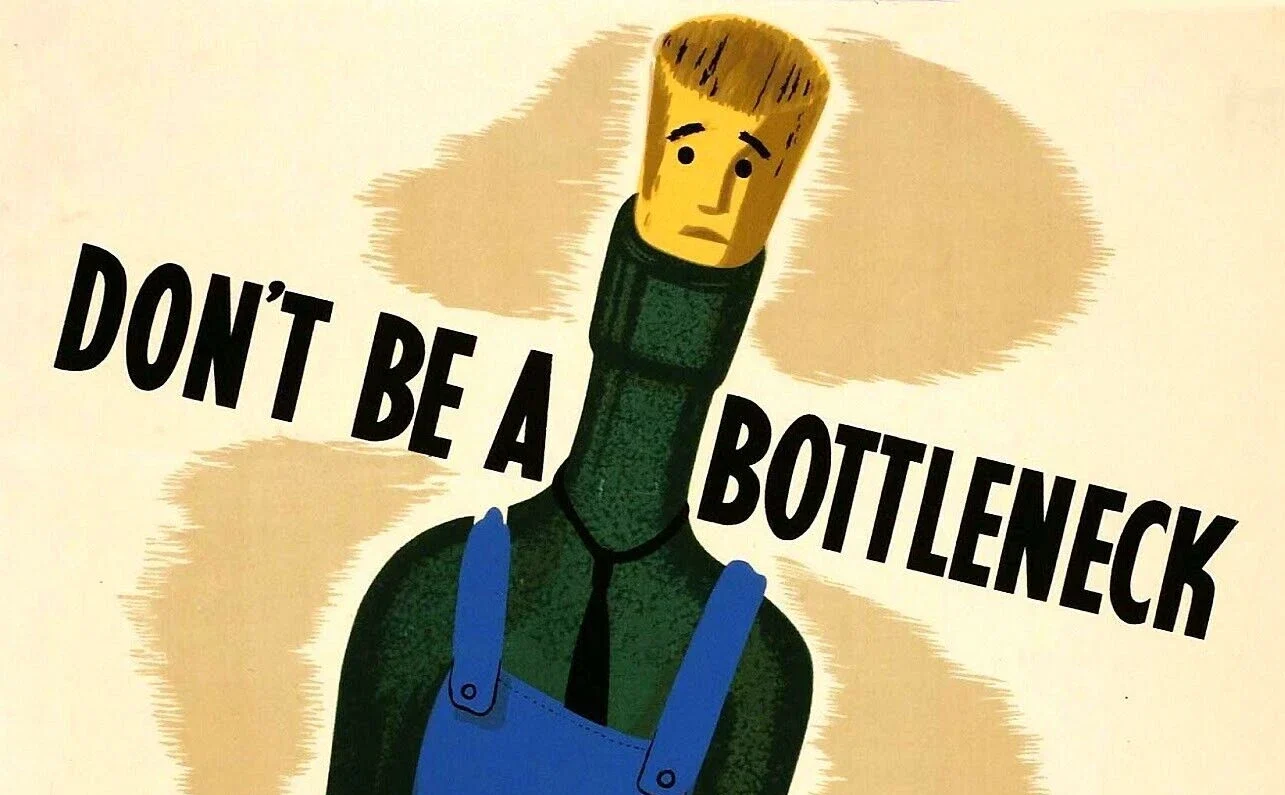

In every case, the structure is the same: capacity is there, but private money says no. Talented organizers, journalists, and public servants are ready. Coalitional energy is real. Democratic desire is present. But political imagination stalls at the threshold of private investment. The assumption that only billionaires or suburban taxpayers can provision democracy has become so entrenched that it is easier to imagine acquiescing to authoritarianism than bypassing this veto.

Such resignation marks the disgrace of our present moment. We live in a democracy with boundless capacity, yet it is held hostage—openly and in bad faith—by private money and the austerity habits it demands. If democracy fails, it will not be because the public’s appetite was absent, but because we accepted private money’s “no” at face value. Even when the mask has long since slipped, and the idea that “the market” demands austerity is a bad joke.

The Neoliberal Habit of Acquiescence

This is the reflex Trump has hijacked. His sabotage of institutions works not only through brute force, but through the learned helplessness that neoliberal governance has drilled into liberals and even leftists for decades. For nearly half a century, Democrats have been told to treat fiscal sabotage as an impersonal event—something to adapt to, never contest. Capital flight, credit downgrades, and market volatility were cast not as acts of power but as external shocks demanding austerity management. Globalization was pitched in these terms: a sublime, external event beyond human governance, against which the only rational stance was flexibility and humility.

Trump exploits this governing reflex and turns it into spectacle. He models himself on the old specter of the “bond vigilante”: an actor so wealthy and unaccountable that he appears as a force of nature, bending governments to his will. Trump embodies that threat in human form, turning sabotage into a performance of independence. His violations of law and democratic norms are staged not as corruption, but as confirmation that he is beholden to no one.

When Democrats treat this as just another crisis to be managed, they recycle the very habit that neoliberalism instilled: the belief that adaptability in the face of sabotage is the essence of responsible governance. To accept private money’s veto is to naturalize political sabotage. What was once presented as adaptation to markets has become collaboration with authoritarianism.

Starmerism & The Private Investment Trap

If neoliberal governance made sabotage appear natural, today’s Democratic politics takes the lesson even further: it treats Trump’s bullying as the new horizon of fiscal life. What once appeared as the sublime discipline of “the market” has been unmasked as the unbounded whims of an increasingly fascistic group of billionaires, with Trump as their avatar. Yet Democrats continue to orient themselves as if nothing essential has changed—adapting to threats as though they were impersonal shocks, rather than deliberate acts of sabotage.

This is just Starmerism: a politics defined not by vision but by compliance, where electoral ambition shrinks to whatever billionaires, suburban taxpayers, or Trump’s manufactured crises will tolerate. The result is a politics of pre-emptive surrender: leaders advertising their moderation not in contrast to authoritarianism, but in deference to the veto power of money and the theater of sabotage. Meanwhile, the public appetite for immediacy is palpable. Each time a non-Trump timetable appears, the response is instant—as when Zohran Mamdani’s proto–public works scavenger hunt drew overwhelming participation. As I argued earlier in Money on the Left, people are not waiting for Trump’s next move; they are rehearsing a desire to be met.

Organizers and campaigns can mobilize small donors in unprecedented numbers, yet the infrastructure of long-term investment—media institutions, public communications, policy experimentation—remains chained to elites who are either hostile or indifferent. The most talented journalists in the country are between jobs, the most creative campaigns run on fumes, and state and city governments are left to administer austerity with nothing but temporary patches. Meanwhile, the only steady stream of cash in politics flows to projects of retrenchment: centrist think tanks, corporate-friendly candidates, and the staging grounds of sabotage.

This is not fiscal realism. It is self-inflicted austerity, the result of imagining sabotage itself as an inescapable condition of democratic life. The paradox of Starmerism is that it presents itself as pragmatic but is in fact the most utopian position of all: it assumes that billionaires and their enforcers can be persuaded to underwrite democracy, against all evidence.

The task now is to break free from this trap—not by waiting for private money to say yes, but by building circuits of democratic credit that bypass its veto altogether.

Even the migration to BlueSky, with its slower rhythms and sometimes too-earnest exchanges, is evidence to this point. Despite the notorious difficulties of platform migration in a socially embedded world, 39 million people have given BlueSky a shot. What this shows is a shockingly robust desire for a public sphere insulated from far right news cycles, where discourse as a public capacity is not dominated by reactionary slop. This is the same public desire that fiscal insurgency can meet—and much better than BlueSky does. A democratic timetable not dictated by private money’s veto or by authoritarian crackdowns, but by the courage to build and sustain public life directly.

That desire is not without precedent. At moments of democratic crisis in the past, Americans have built new circuits of credit and coordination to bypass elite vetoes.

Historical Precedents for Fiscal Insurgency

Insurgent credit has always been American democracy’s lifeblood, emerging time and again when all else fails.

The most famous example is the Greenback. During the Civil War, when private banks could not—or would not—provision the Union’s survival, the government issued its own money directly. These notes were not backed by gold or private wealth but by the promise of democratic governance. They bypassed the Jacksonian gold standard and private banking alike, and proved that fiscal capacity could be mobilized without elite consent. For a generation afterward, Greenbackers carried that lesson forward, insisting that democratic credit could fund not only war but schools, infrastructure, and social flourishing.

A similar logic returned in World War II. Faced with the need to mobilize resources on a scale without precedent, the U.S. government issued war bonds that transformed ordinary households into participants in the nation’s fiscal life. These bonds were not simply instruments of finance; they were instruments of mass coordination. Posters, rallies, and public campaigns framed bond-buying as an act of civic belonging, turning fiscal issuance into a cultural project. The war effort was provisioned not by waiting for private investment to return during the Great Depression, but by enrolling the public directly into circuits of democratic credit.

Money on the Left’s “Blue Bonds” proposal updates this history for our own authoritarian crisis. Blue Bonds are a way for states and cities to issue credit directly in the form of a national bond drive that insulates democratic institutions from hostile federal sabotage. Their structure is the famous duck-rabbit illusion: they can appear as conventional borrowing duck within a neoliberal framework, or as a credit instrument rabbit that unlocks public capacity in a democratic framework. Either way, the effect is the same: institutions provision themselves and democracy writ large, bypassing the veto of billionaires and the sabotage of Trump.

In the same spirit, complementary currencies offer a local and coalition-based approach: unions, campaigns, and municipalities can provision one another directly, rehearsing democratic solidarity through circuits of receivability rather than dependence on hostile elites.

These experiments matter not because they are perfect or permanent, but because they reveal a principle: democracy does not have to wait on private money. At key moments, Americans have already built and lived within systems of public credit that bypassed entrenched vetoes. Today’s challenge is to remember that history and mobilize it—to see in Greenbacks, war bonds, Blue Bonds, and complementary currencies not oddities of fiscal history, but usable precedents for democratic survival.

Fiscal Insurgency as Public Endurance

Fiscal insurgency is not isolation. It is not about retreating into localism or walling off states from the national economy. It is about building protective circuits of credit that keep democratic life functioning even when sabotage is staged from above. Insulation means refusing to let billionaires or authoritarian actors dictate the terms of survival.

The Greenbacks insulated the Union from the constraints of the Jacksonian gold standard and private banking. World War II bonds insulated the war effort from failing private investment by activating public capacity directly. Blue Bonds extend this logic, creating coordinated fiscal capacity across states and cities that cannot be held hostage to federal obstruction. Complementary currencies, in turn, can provide insulation at the community level—allowing campaigns, unions, and municipalities to sustain each other when donor strikes or hostile legislatures attempt to cut them off.

What unites these experiments is their orientation toward endurance. They do not dissolve political conflict, though they do reveal markets to be corrupt betting institutions with often very little relation to our collective needs and capacities. Insulation means treating fiscal capacity as a public utility, not a private concession. It means provisioning schools, universities, media, and public works on terms that cannot be vetoed by billionaires or broken by Trump’s shakedowns.

To demand insulation, then, is not to run from political economy but to govern it—to make sure that democratic credit flows even when elites attempt to dam it. In this sense, fiscal insurgency is not only possible but necessary: it is how democracy is renewed.

Democracy or Acquiescence

The stakes are not a simple fork between two univocal paths. What is at issue are competing habits of orientation that press on institutions, coalitions, and publics all at once. Acquiescence registers sabotage as shock and awe and then mistakes that registration for reality—treating crises as external facts, measuring competence by austerity management, and advertising moderation in deference to oligarchs and dictators. These habits make collaborators out of people and institutions that imagine themselves merely adapting to circumstance.

Progressives are not exempt. Too often, they defer fiscal action to manufactured chokepoints: until national electoral victories return power to Democrats, until taxpayers can be persuaded to recycle their salaries into the state, until enlightened billionaires decide to bankroll media or infrastructure. Each deferral helps normalize acquiescence as realism, training institutions to accept sabotage as governance.

Yet when people crown an insurgent political campaign with star-power and charisma, participate in a playful scavenger hunt, or even migrate to slower platforms like BlueSky, they rehearse another orientation: one that insists capacity is abundant, desire is real, and democracy does not have to wait. These moments do not resolve into a single coherent path; they are plural rehearsals of another public life. Fiscal insurgency is how these scattered desires are enacted at a meaningful scale—how democratic improvisations become durable circuits of public credit.

The disgrace is not that Trump is strong, but that so many continue to bow before private money’s veto even as it is unmasked as blackmail and collusion. The task is to cultivate and extend the democratic reflex wherever it appears, multiplying its legibility, and provisioning the health of our democracy rather than allowing sabotage to dictate the terms of survival.

Say Yes

Bouie, Carvell, and Collins are right: the talent, energy, and capacity are already here. The organizers are ready, the journalists are waiting, the public appetite is palpable. What blocks the way is not imagination, but private money’s refusal—backed by a political culture that treats that refusal as final.

Fiscal insurgency is the way to break that habit. It is how we turn capacity into action without waiting for billionaire patronage or taxpayer permission slips. It is how we refuse the manufactured chokepoints that fracture coalitions and empower Trump. It is how we insulate democracy from sabotage long enough to renew it. That is all that endogenous money really is: the courage to issue it, met by a public capacity that has already rehearsed its legitimacy.

The refrain of our moment—capacity is there, but money says no—should no longer be a lament. It must become a call. Private money’s “no” is not natural, it is not inevitable, and it is not the last word. We have the precedents, we have the tools, and we have the urgency. What remains is to build the circuits of public credit that can say yes to democracy when private power will not.

[…] required to provide for basic needs. Will Beaman highlights this vulnerability in his argument for fiscal insurgency, noting that the political viability of progressive public projects is often threatened by […]

[…] only to resist Wall Street’s structural veto, but also to reframe New York’s bonds as instruments that mobilize unions, pensions, and […]